CRL Wiki:Main Page

UW Climate Risk Lab

“Making the best climate risk data, analysis and tools available for all.”

About

The UW Climate Risk Lab (CRL) is a multidisciplinary research and innovation center based at the University of Washington Foster School of Business in the Department of Finance & Business Economics. Established in 2022, it advances data and technology solutions to issues in climate-related financial risk for corporate and government decision-makers. Phillip Bruner, co-founder of the CRL, currently serves as its Executive Director.

The CRL brings together academics and professionals in climate finance, risk management, business analytics, data engineering, computer science, atmospheric sciences, supply chains management, information systems and AI. It collaborates with several initiatives within the University of Washington (UW), which include the Buerk Center for Entrepreneurship, Clean Energy Institute, Creative Destruction Lab, eSciences Institute and Urban Infrastructure Lab. Its external partners include: the Duke Energy Data Analytics Lab, the Pacific Northwest Mission Accelerator Center, and Washington Maritime Blue.

History

The CRL originated in 2022 with a grant from the Office of UW President Ana Marie Cauce made to the Foster School of Business, Department of Finance & Business Economics. The idea was then developed by a team lead by Phillip Bruner, UW Professor of Sustainable Finance, Charlie Donovan, Senior Economic Advisor at Impax Asset Management, Sam Shugart, New Product & Services Market Analyst at Puget Sound Energy and Simon Park, Harvard graduate and Fellow of the UW Evans School of Public Policy.

Steering Committee

The CRL Steering Committee is currently made up of the following members:

Phillip Bruner, Professor of Sustainable Finance and CRL Executive Director

Léonard Boussioux, Assistant Professor of Information Systems and Operations Management

Charlie Donovan, Senior Economic Advisor at Impax Asset Management and CRL Leadership Council Chair

Emer Dooley, Artie Buerk Faculty Fellow and Site Lead at Creative Destruction Lab

Dale Durran, Professor of Atmospheric Sciences and Adjunct Professor of Applied Mathematics

Kristie Ebi, Professor of Global Health and Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences and Founder of the UW Center for Health and the Global Environment

Sara Jones, Director of the Masters of Supply Chain Management and Master of Science in Business Analytics

Dan Schwartz, Boeing-Sutter Professor of Chemical Engineering and Founding Director of the Clean Energy Institute

Jan Whittington, Associate Professor of the Department of Urban Design and Planning and Founding Director of the Urban Infrastructure Lab

What is climate risk?

Climate risk is the potential for negative consequences for human or ecological systems from the impacts of climate change. [1] It refers to risk assessments based on formal analysis of the consequences, likelihoods and responses to these impacts and how societal constraints shape adaptation options. [2] [3] The science also recognizes different values and preferences around risk, and the importance of risk perception. [4]

Common approaches to risk assessment and risk management strategies based on natural hazards have been applied to climate change impacts although there are distinct differences. Based on a climate system that is no longer staying within a stationary range of extremes, [5] climate change impacts are anticipated to increase for the coming decades. Ongoing changes in the climate system complicate assessing risks. Applying current knowledge to understand climate risk is further complicated due to substantial differences in regional climate projections. There is also an expanding number of climate model results, and the need to select a useful set of future climate change scenarios in the assessments.[6]

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment framework is based on the understanding that climate risk emerges from the interaction of three risk factors: hazards, vulnerability and exposure. The IPCC summarizes published research on climate risk evaluations. [7] International and research communities have been working on various approaches to climate risk management including climate risk insurance.

Climate change is a medium- to long-term trend that is expected to have significant financial impacts on companies in affected industries, including on their credit profiles and/or share prices. However, this knowledge is not particularly helpful for lenders, investors, or regulators unless these climate-related financial risks can be further defined in terms of their scope and, more importantly, their timing and likelihood. It is necessary to identify climate risks to industries before they cause reductions in asset utilization or valuation, reduced income and margins, or other financial impacts—changes that translate into credit risk and influence lenders’ decisions about financial profiles. [8]

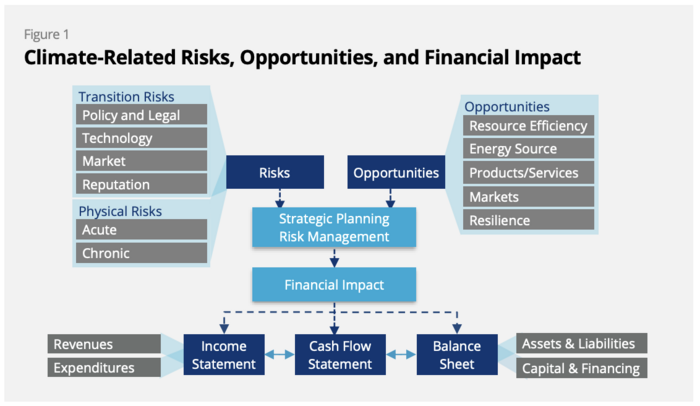

There are two categories of climate-related financial risk, according to the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD): [9]

- Transition Risks: Risks related to the transition to a lower-carbon economy.

- Physical Risks: Risks related to the physical impacts of climate change.

Source: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

Transition risks

Transition risks are those associated with the pace and extent at which an organization manages and adapts to the internal and external pace of change to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and transition to renewable energy. Transitioning requires policy and legal, technology, and market changes to address mitigation and adaptation requirements related to climate change (see Table 1). Depending on the nature, speed, and focus of these changes, transition risks may pose varying levels of financial and reputational risk to organizations (see Table 2). Alternatively, if an organization is a low-carbon emitter and in the renewable energy or climate transition market, they could experience market, technological, and reputational opportunities.

| Transition Risk Categories | |

|---|---|

| Policy and Legal | Policy actions around climate change continue to evolve. Their objectives generally fall into two categories—policy actions that attempt to constrain actions that contribute to the adverse effects of climate change or policy actions that seek to promote adaptation to climate change. The risk associated with and financial impact of policy changes depend on the nature and timing of the policy change. As the value of loss and damage arising from climate change grows, litigation risk is also likely to increase. Reasons for such litigation include the failure of organizations to mitigate impacts of climate change, failure to adapt to climate change, and the insufficiency of disclosure around material financial risk my s. |

| Technology | Technological improvements or innovations that support the transition to a lower-carbon, energy efficient economic system can have a significant impact on organizations. To the extent that new technology displaces old systems and disrupts some parts of the existing economic system, winners and losers will emerge from this "creative destruction" process. The timing of technology development and deployment, however, is a key uncertainty in assessing technology risk. |

| Market | While the ways in which markets could be affected by climate change are varied and complex, one of the major ways is through shifts in supply and demand for certain commodities, products, and services as climate-related risks and opportunities are increasingly considered. |

| Reputation | Climate change has been identified as a potential source of reputational risk tied to changing customer or community perceptions of an organization's contribution to or detraction from the transition to a lower-carbon economy. |

Source: This table's content is reproduced from Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

| Climate-related Transition Risks | Potential Financial Impacts |

|---|---|

| Policy and Legal | |

|

|

| Technology | |

|

|

| Market | |

|

|

| Reputation | |

|

|

Source: This table's content is reproduced from Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

Physical risks

Physical risks are those associated with the impacts from climate change. These risks can be event driven (acute) or associated with longer-term shifts in climate patterns (chronic), as described in Table 3

| Physical Risk Categories | |

|---|---|

| Acute | Acute physical risks refer to those that are event-driven, including increased severity of extreme weather events, such as cyclones, hurricanes, heat or cold waves, or floods. |

| Chronic | Chronic physical risks refer to longer-term shifts in climate patterns (e.g., sustained higher temperatures, sea level rise, changing precipitation patterns) that may cause sea level rise or chronic heat waves. |

Source: This table's content is reproduced from Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

Physical risks may have financial implications for organizations, such as direct damage to assets and indirect impacts from supply chain disruption. Organizations' financial performance may also be affected by changes in water availability, sourcing, and quality; food security; and extreme temperature changes affecting organizations' premises, operations, supply chain, transport needs, and employee safety. Table 4 presents examples of climate-related physical risks and financial impacts.

| Climate-related Physical Risks | Potential Financial Impacts |

|---|---|

|

Acute

Chronic

|

|

Source: This table's content is reproduced from Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

License Information

This website’s content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

You are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format for any purpose, even commercially.

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially.

- The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

Notices:

- You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation.

- No warranties are given. The license may not give you all of the permissions necessary for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rights may limit how you use the material.

Read the full license here.

References

- ↑ IPCC, 2022: Annex II: Glossary [Möller, V., R. van Diemen, J.B.R. Matthews, C. Méndez, S. Semenov, J.S. Fuglestvedt, A. Reisinger (eds.)]. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O.Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 2897–2930, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.029.

- ↑ Adger WN, Brown I, Surminski S (June 2018). "Advances in risk assessment for climate change adaptation policy". Philosophical Transactions. Series A, Mathematical, Physical, and Engineering Sciences. 376 (2121): 20180106. Bibcode:2018RSPTA.37680106A. doi:10.1098/rsta.2018.0106. PMC 5938640. PMID 29712800.

- ↑ Eckstein D, Hutfils M, Winges M (December 2018). Global Climate Risk Index 2019; Who Suffers Most From Extreme Weather Events? Weather-related Loss Events in 2017 and 1998 to 2017 (PDF) (14th ed.). Bonn: Germanwatch e.V. p. 35. ISBN 978-3-943704-70-9. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ↑ Ara Begum, R., R. Lempert, E. Ali, T.A. Benjaminsen, T. Bernauer, W. Cramer, X. Cui, K. Mach, G. Nagy, N.C. Stenseth, R. Sukumar, and P. Wester, 2022: Chapter 1: Point of Departure and Key Concepts. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 121–196, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.003.

- ↑ IPCC (2018). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report. Summary for Policymakers (PDF). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. p. 5.

- ↑ Whetton P, Hennessy K, Clarke J, McInnes K, Kent D (2012-12-01). "Use of Representative Climate Futures in impact and adaptation assessment". Climatic Change. 115 (3): 433–442. Bibcode:2012ClCh..115..433W. doi:10.1007/s10584-012-0471-z. S2CID 153833090

- ↑ About — IPCC". Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ↑ Imperial College Business School Center for Climate Finance & Investment (February 2022). “What is Climate Risk? A Field Guide for Investors, Lenders, and Regulators.” Available at: https://imperialcollegelondon.app.box.com/s/te5eahz3x47q93vufwwu3ntmf5rxecxs

- ↑ Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (June 2017). “Recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures: Final Report.” Available at: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report.pdf