Physical Risk

Introduction

Physical risks are risks associated with the physical impacts of a changing climate, including the risk of destruction of assets and/or disruption of operations, trade routes, supply trains, and markets. These risks can be event driven (acute) or associated with longer-term shifts in climate patterns (chronic), as described in Table 3.

| Physical Risk Categories | |

|---|---|

| Acute | Acute physical risks refer to those that are event-driven, including increased severity of extreme weather events, such as cyclones, hurricanes, heat or cold waves, or floods. |

| Chronic | Chronic physical risks refer to longer-term shifts in climate patterns (e.g., sustained higher temperatures, sea level rise, changing precipitation patterns) that may cause sea level rise or chronic heat waves. |

Source: This table's content is reproduced from Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

Physical risks may have financial implications for organizations, such as direct damage to assets and indirect impacts from supply chain disruption. Organizations' financial performance may also be affected by changes in water availability, sourcing, and quality; food security; and extreme temperature changes affecting organizations' premises, operations, supply chain, transport needs, and employee safety. Table 4 presents examples of climate-related physical risks and financial impacts.

| Climate-related Physical Risks | Potential Financial Impacts |

|---|---|

Acute

Chronic

|

|

Source: This table's content is reproduced from Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

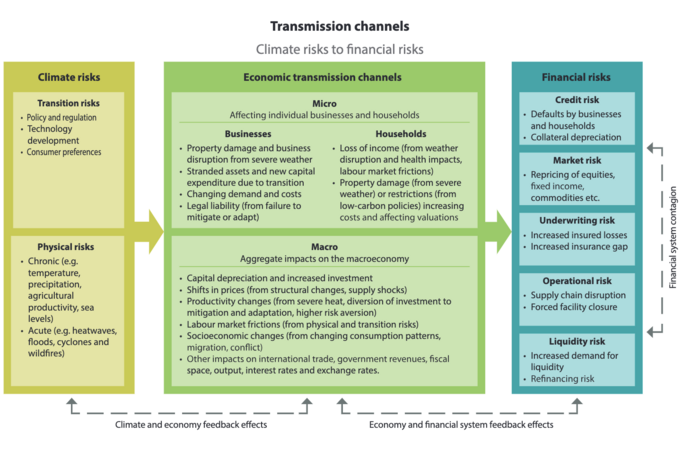

Transmission Channels

Climate change can affect the financial system through various micro and macro transmission channels (Figure 1).[1] Climate hazards such as wildfires and floods can affect individual businesses and households via directly damaging the property, assets, and means of production. Climate policies and new technologies can influence the profitability of businesses and the wealth of households, creating financial risks for lenders and investors. In addition, climate change can reshape the broader economic environment, indirectly affecting the financial sector. For instance, climate-related policies and regulations may redirect investments, alter the pricing of renewable and traditional energy, and consequently impact the capital valuations of companies holding these assets.

Large-scale climate hazards can also generate significant macroeconomic consequences beyond the immediate area of impact. The direct damage to assets, infrastructure, and production lines in affected regions disrupts productive activities, which can lead to broader economic effects, including reductions in employment, production, and investment, as well as challenges for public finances, such as fiscal revenue losses and debt sustainability concerns. These disturbances can also impair a country’s financial sector, contributing to credit, market, and operational risks, and influencing financial stability indicators.

The cascading effects of these disruptions can harm financial performance at multiple levels—across sectors, individual assets, firms, and business lines. As a result, both direct and indirect pathways of risk must be considered for effective financial risk management, even at the firm level. For instance, Bressan et al. (2024)[2] provide an example of firm-level climate financial impact assessment, incorporating both asset-level climate risks and the resulting macroeconomic effects.

Assessment Methodology

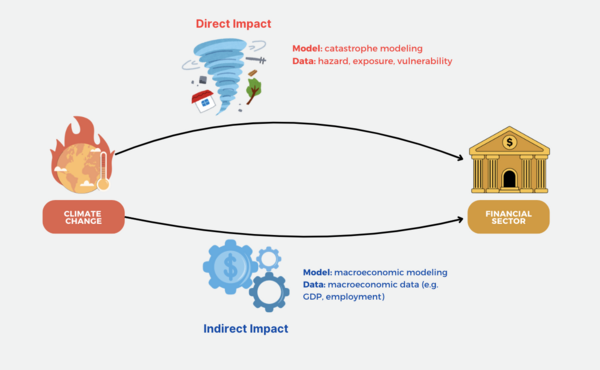

Climate change impacts financial systems both directly and indirectly (Fig. 2).[3] Direct damages refer to immediate to short-term physical destruction, including destruction of housing, critical infrastructure, and means of production which results in direct financial loss. Indirectly, climate hazards affect the financial sector via impacting the macroeconomic environment (see Transmission channels).

Direct damages, primarily at the asset level, are typically assessed using a traditional risk assessment framework proposed by the IPCC[4][5] where risk is defined as the product of the climate and weather-related hazards, the exposure of goods or people to this hazard, and the specific vulnerability of exposed people, infrastructure, and environment (Fig. 3). This is often done through a catastrophe modeling approach which integrates climate hazard information with exposure and vulnerability metrics to estimate the financial cost of physical damage (or “losses”) to a geographically specific portfolio of physical assets.

A catastrophe model typically includes three main components: a hazard module, which assesses the extent and intensity of climate hazards; a vulnerability module, which relates hazard to physical damage; and a financial module that translates physical damage to financial losses.[6][7] [8]The key output of a catastrophe model is the distribution of possible losses, expressed in financial terms, to the portfolio. Scenario analysis, often implemented using Monte Carlo simulations as seen in models like CLIMADA, is also usually embedded in catastrophe models where the events are modeled thousands of times with slight modifications each time to reflect the overall likely distribution of losses due to inherent uncertainty in those estimates. See the Tools and Models section for lists of open-source catastrophe models.

The indirect impacts are estimated by macroeconomic models which capture how the direct damages propagate and interact with other sectoral and macroeconomic variables over time. These models require key macroeconomic indicators, such as GDP, employment, household consumption, trade flows, and country-specific socioeconomic data, to assess broader economic consequences. Examples of commonly used models are provided in the Tools and Models section.

References

- ↑ NGFS (2023). NGFS Scenarios for central banks and supervisors. Available at: https://www.ngfs.net/sites/default/files/medias/documents/ngfs_climate_scenarios_for_central_banks_and_supervisors_phase_iv.pdf

- ↑ Bressan, G., Đuranović, A., Monasterolo, I. et al. Asset-level assessment of climate physical risk matters for adaptation finance. Nat Commun 15, 5371 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48820-1

- ↑ Bavandi,Antoine; Berrais, Dorra; Dolk,Michaela Mei; Mahul,Olivier. Physical Climate Risk Assessment : Practical Lessons for the Development of Climate Scenarios with Extreme Weather Events from Emerging Markets and Developing Economies - Technical Document (English). Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099657511082325958/IDU0004b1eec0d7f304e7c0967305183f75f92a2

- ↑ IPCC: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P. R. Mastrandrea, and L. L. White, Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA., 2014.

- ↑ IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 35-115, doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.

- ↑ Note that variations in catastrophe modeling exist. For example, in the "Double Trouble? Assessing Climate Physical and Transition Risks for the Moroccan Banking Sector" by the World Bank, financial module is omitted and an exposure module is included in the catastrophe model. In the "Physical risk framework: Understanding the impact of climate change on real estate lending and investment portfolios"report by the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, however, exposure is treated as an input.

- ↑ World Bank. Double Trouble? Assessing Climate Physical and Transition Risks for the Moroccan Banking Sector (English). Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099040924013528667/P175074139948c00a1ae591466b51bbb4d6

- ↑ Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL). (2019, February). Physical risk framework: Understanding the impacts of climate change on real estate lending and investment portfolios. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership.