Marine Heatwaves

Overview

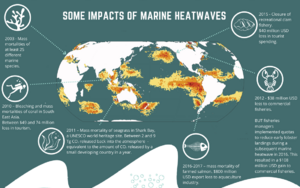

Marine heatwaves (MHWs) are periods of extreme warm ocean temperature that persist for days to months, can extend up to thousands of kilometers and can penetrate multiple hundreds of meters into the deep ocean[1]. (IPCC) They have significant impacts on marine ecosystems, as well as physical and human system (or called coastal communities and economies). MHWs have negatively impacted marine organisms and ecosystems in all ocean basins over the last two decades, including critical foundation species such as corals, seagrasses and kelp. Impacts include coral bleaching and mortality, loss of seagrass and kelp forests, shifts in species range, and local and potentially global extinctions of coral species. MHWs can also cause major economic losses through impacts on fisheries and aquaculture (Figure 1).

These phenomena have a strong impact not only at the global and regional level (e.g., substantial events in the Northeast Pacific (2013-15), Mediterranean Sea (2003) and Tasman Sea (2015/16 and 2017/18)), but also at the local level. In this sense, MHWs have become an increasingly serious threat not just from the perspective of pelagic and benthic ecology on the continental shelf but also for coastal aquaculture and fisheries, as demonstrated by many reports of fisheries closures from around the world caused by MHWs.

Impacts: Major MHWs have had significant impacts on a wide range of species, from plankton to fish to sea birds, by affecting biological processes such as growth, reproduction and survival (Smale et al. 2019). For example, the ‘Blob’ – a massive long-lasting MHW that developed in the northeast Pacific in 2014 – disrupted the entire foodweb and led to mass die offs of sea birds and mammals (Smith et al. 2021). Rogue animals can also find their way well outside their normal range, following the warm waters of a MHW, such as this tropical fish found off Tasmania during the 2015/16 event. Attach the picture as well [2]

Marine heatwaves are periods of persistent anomalously warm ocean temperatures, which can have significant impacts on marine life as well as coastal communities and economies. MHWs are a growing field of study worldwide because of their effects on ecosystem structure, biodiversity, and regional economies.

Marine heatwaves have become an urgent issue regarding climate risks due to their increase in frequency, duration, magnitude, and spatial extent. The number of MHW days has doubled between 1982 and 2016[3], and they have become more longer-lasting, more intense, and more extensive -- 8 of the 10 most severe recorded events have taken place in the past decade[4]. MHWs are projected to further increase with global warming. Climate models project increases in the frequency of marine heatwaves by 2081-2100, relative to 1850–1900, by approximately 50 times under RCP8.5 and 20 times under RCP2.6. The intensity of marine heatwaves is projected to increase about 10-fold under RCP8.5 by 2081–2100, relative to 1850–1900[1].

Data

Definition of MHW: Our group developed a definition of MHWs (Hobday et al. 2016), which has been widely adopted by researchers and other users. A MHW is defined as a period when seawater temperatures exceed a seasonally-varying threshold (usually the 90th percentile) for at least 5 consecutive days. Successive events with gaps of 2 days or less are considered part of the same MHW. In a subsequent study (Hobday et al. 2018) we extended the definition to introduce categories of severity, based on multiples of the threshold being exceeded. [5]

Historical:

Observations: MHW tracker:

past events of California MHW: https://www.integratedecosystemassessment.noaa.gov/regions/california-current/california-current-marine-heatwave-tracker-blobtracker

SST Datasets at PSL[6]

- NOAA OI SST Daily High Resolution. From 1982, a gridded high resolution daily dataset from NOAA that continues to present.

- NOAA ERSST V5 From 1865, a gridded consistently analyzed monthly dataset from NOAA that continues to present. V3 and V4 are also available

- COBE SST

- COBE-2 SST

- ICOADS

- Kaplan SST

- NOAA OI V2

- NODC 1994 and 1998 atlasses

Forecast:

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Collins M., M. Sutherland, L. Bouwer, S.-M. Cheong, T. Frölicher, H. Jacot Des Combes, M. Koll Roxy, I. Losada, K. McInnes, B. Ratter, E. Rivera-Arriaga, R.D. Susanto, D. Swingedouw, and L. Tibig, 2019: Extremes, Abrupt Changes and Managing Risk. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 589-655. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964.008.

- ↑ https://www.marineheatwaves.org/mhw-impacts.html

- ↑ Frölicher, T.L., Fischer, E.M. & Gruber, N. Marine heatwaves under global warming. Nature 560, 360–364 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0383-9

- ↑ Smith, Kathryn E., et al. "Socioeconomic impacts of marine heatwaves: Global issues and opportunities." Science 374.6566 (2021): eabj3593.

- ↑ https://www.marineheatwaves.org/mhw-overview.html

- ↑ https://psl.noaa.gov/marine-heatwaves/#