Marine Heatwaves

Overview

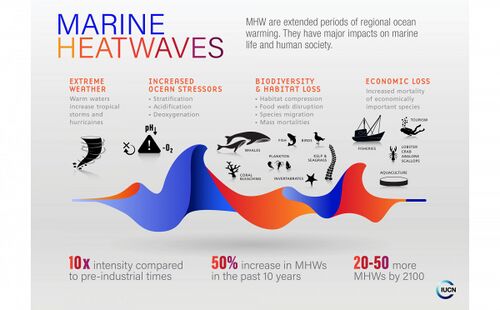

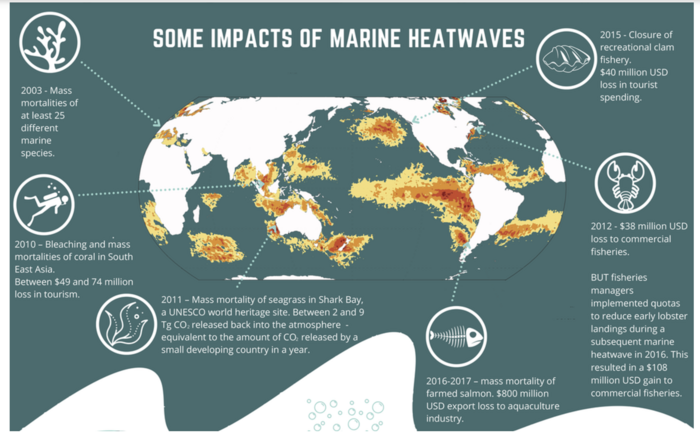

Marine heatwaves (MHWs) are periods of extreme warm ocean temperature that persist for days to months, extend over thousands of kilometers, and penetrate multiple hundreds of meters into the deep ocean[2]. These extreme high temperatures can cause billions of dollars' economic losses by negatively impacting the critical ocean ecosystems (Figure 1).

Over the past three decades, MHWs have adversely affected marine organisms and ecosystems in all ocean basins, including critical foundation species like corals, seagrasses, and kelp. They have led to widespread coral bleaching and mortality, dieback of kelp forests and seagrasses, and harmful algal blooms[2][3]. The disruption of these foundation species destabilizes food webs, leading to significant consequences for fisheries, aquaculture, and tourism industries that depend on them. For example, the prolonged MHW over the northeast Pacific in 2014 severely disrupted the food web, resulting in mass mortalities of California sea lions, seals, seabirds, and marine invertebrates (Smith et al. 2021)[3]. The associated harmful algal blooms led to the closure of recreational razor clamming, causing a $40 million loss in tourist spending in Washington State. Similarly, the closure of commercial Dungeness crab fishing on the West Coast resulted in a total loss of $97.5 million. Additionally, the population decline of red sea urchins due to kelp loss led to the closure of their commercial fishery, resulting in an annual loss of $3 million[3].

MHWs have also been shown to reduce the productivity or cause mortality of economically important species, such as lobster and snow crab in the northwest Atlantic and scallops off Western Australia[4]. For more information on the impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity, please visit the Biodiversity Loss page on the CRL wiki.

Marine heatwaves have become an urgent climate risk due to their increasing frequency, duration, intensity, and spatial extent. The number of MHW days doubled between 1982 and 2016[5], with these events becoming more prolonged, intense, and widespread—8 of the 10 most severe recorded MHWs have occurred in the past decade[3]. Projections indicate that MHWs will continue to intensify with global warming. Climate models suggest that by 2081-2100, the frequency of MHWs could increase by approximately 50 times under the high-emission scenario (RCP8.5) and 20 times under the low-emission scenario (RCP2.6) relative to 1850–1900. The intensity of MHWs is projected to increase about tenfold under RCP8.5 by 2081–2100 compared to the 1850–1900 baseline[2].

Data

How to measure marine heatwaves

Hobday et al. (2016)[6] developed a widely adopted definition of marine heatwaves (MHWs). According to this definition, an MHW is a period during which seawater temperatures exceed a seasonally varying threshold (typically the 90th percentile) for at least five consecutive days. Successive events with gaps of two days or less are considered part of the same MHW. Here are links to code implementations of the MHW definition by Hobday et al. (2016) in Python and R.

As a general guideline, an anomaly of 1 degree Celsius (roughly 2 degrees Fahrenheit) off the coast of California can indicate a marine heatwave, while anomalies of 2-3 degrees Celsius (approximately 4-6 degrees Fahrenheit) are indicative of more extreme marine heatwave events[7].

Relevant datasets to calculate marine heatwaves

- NOAA OI SST from 1982, a gridded high-resolution (0.25 degree) daily global sea surface temperature dataset from NOAA that continues to present.

- NOAA ERSST V5 from 1865, a gridded (2.0 degree) consistently analyzed monthly global sea surface temperature dataset from NOAA that continues to present.

- NOAA - hourly position, current, and sea surface temperature from drifters from 1987 (AWS data access here).

Current observations

- Marine heatwave tracker by Marine Heatwave International Working Group

- Marine heatwave observations by NOAA

Past California current marine heatwave events

- Detailed information (i.e., size, duration, distance from shore) of past marine heatwave events

- Animations of yearly sea surface temperature anoamlies

Forecasts

- Forecasts up to 11.5 months ahead by Jacox et al. (2002)[8]

References

- ↑ Retrieved from https://iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/marine-heatwaves on October 24, 2024.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Collins M., M. Sutherland, L. Bouwer, S.-M. Cheong, T. Frölicher, H. Jacot Des Combes, M. Koll Roxy, I. Losada, K. McInnes, B. Ratter, E. Rivera-Arriaga, R.D. Susanto, D. Swingedouw, and L. Tibig, 2019: Extremes, Abrupt Changes and Managing Risk. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 589-655. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964.008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Smith, Kathryn E., et al. "Socioeconomic impacts of marine heatwaves: Global issues and opportunities." Science 374.6566 (2021): eabj3593.

- ↑ https://www.marineheatwaves.org/mhw-impacts.html

- ↑ Frölicher, T.L., Fischer, E.M. & Gruber, N. Marine heatwaves under global warming. Nature 560, 360–364 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0383-9

- ↑ Hobday, Alistair J., Lisa V. Alexander, Sarah E. Perkins, Dan A. Smale, Sandra C. Straub, Eric CJ Oliver, Jessica A. Benthuysen et al. "A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves." Progress in oceanography 141 (2016): 227-238.

- ↑ https://scripps.ucsd.edu/research/climate-change-resources/californias-marine-heatwaves

- ↑ Jacox, M.G., Alexander, M.A., Amaya, D. et al. Global seasonal forecasts of marine heatwaves. Nature 604, 486–490 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04573-9